Discovered some papers in a crate in the basement. It's Box No. 10, according to my mom's impressively detailed catalogue of the junk room's possessions. School papers, graduation stuff, the results of my driver's test, taken on July 19, 1991. I pretty much aced it, scoring "good" in every category except for right turns, where I performed poorly when approaching and entering the lanes. How did I screw up one of the easiest things on the test? I don't recall.

Driver's training had been challenging. We took a class in the fourth quarter of our freshman year and received on-the-road training during the summer. I was partnered up with a kid who'd been driving since he was like 11 years old, when he stole a car and took a joy ride around town. He became something of a rebel legend after that incident. He had such confidence behind the wheel. I envied him. He all but cruised the bad streets of Janesville with his right arm draped around our instructor's neck, as if the teacher was his girl on a Friday night date. The kid owned moves behind the wheel Earnhardt Senior couldn't have pulled off. My car experience consisted of bumper cars at the Janesville Hay Daze - which once ended with a carnie rescuing me because I couldn't operate the vehicle - and a disastrous incident where I backed my parents' car out of their tiny garage and drilled the driver's side door as my dad stared in disbelief and, well, fury.

But by the time the driver's test came a year later, I had conquered my demons, and the exam.

The box in the basement also holds all of the science experiments I conducted in seventh-grade. There was a "soil lab report," which I decorated in blue cardboard paper and a front-page drawing that looks like something scribbled by a blind child or a troubled one. My group concluded that "our soil was sand. Day six was the ribbon test. Our soil did not make a ribbon which also means it's probably sand. Our texture again was gritty." Salk's seventh-grade reports showed similar insights. We scored a B, due to some shoddy explanations, though our final conclusion was absolutely correct. It was sand, damn it.

There was an experiment involving a hamster and a maze. Again, a B, as we didn't adequately explain how "Martha" learned over the course of 20 trials. Without interviewing Martha, how exactly were we supposed to discover her thought process?

Finally there's a report I conducted alone. I titled the paper "Good Vibrations," an homage to the Beach Boys and lovers of bad puns. On the cover I drew a rough facsimile of a minnow, complete with a thought bubble that read, "Oh no it's the dreaded telesacoil." A telesacoil? Google telesacoil. There's no such thing. Did I mean a Tesla coil? I don't know. The other materials for this experiment were "1 minnow, 2 paper towels, faucet, soap." Thankfully, I spelled all of those words correctly in my paper, though I did break AP style by using figures for numbers under 10.

The extent of the paper:

PROBLEM: To see if the Minnow will react to electricity. (Why did I capitalize minnow?)

INFORMATION: The minnow is a small river fish. It's used for bait and trout food. It has small scales shaped like tiles. (I'm assuming all of that's true, but after seeing telesacoil littering my paper, who knows what other information I made up.)

HYPOTHESIS: I believe that the fish will die when it's shocked with electricity. (Heh.)

PROCEDURE: Step one: Take the minnow out of the jar and lay the minnow on the paper towel. Step two: Take the telesacoil and test it on the faucet then shock the minnow every minute. Step three: record the results. Step four: Clean up.

The fish died. It took eight minutes of torture. He was survived by 445 siblings and a poorly punctuated science report.

Minnow showed no reaction after a minute, before finally beginning to "wiggle around" in the third minute. At minute five, "there is the first sign of blood on the minnow." Blood appears on the head at the seventh minute. Dies at eight. That's it, that's the paper. If I had ever been arrested as a juvenile, the prosecutor would have presented this paper as proof that I needed to be locked up until I turned 21.

"Look at how he enjoys torturing animals, your honor. Yes, we consider the minnow an animal. He even used a perverted version of the scientific method and documented his findings. He combined science and sadism. He needs help."

But this was a real paper. The teacher - the school's volleyball and softball coach who was sort of my nemesis, while also being my family's friendly neighbor - gave me an A-/B+. He liked the work, at least better than my breakthrough studies on sand and mazes.

My conclusion:

"I accept my hypothesis although after the first few minutes I didn't think the minnow would last as long as it did because the minnow was showing no reaction after the first few shocks, but after several other shocks the minnow started to show signs of reacting to the shocks such as bleeding and wiggling around so my final conclusion is that the fish died."

A sixty-five word sentence, with one comma. I was in seventh grade when I wrote that. I was 12 years old, but that writing would be below-average for an 8-year-old. Was a classmate shocking me with a "telesacoil" when I penned my conclusion? Yet I got an A-/B+, which makes me wonder just how bad some of my classmates' experiments and papers were if they received Cs or even Ds. Did my Good Vibrations title impress my teacher so much he ignored my paper's countless faults and questionable taste? On the back of my paper I again drew a fish - poorly - with the words "May He Rest In Peace" written above. I was obviously glib about my involvement in the torture and death of the minnow. My paper even had a dedication page, which I used to thank my friend Brandon, who apparently gave me the idea for the experiment (I don't recall the conversation or setting when he first brought up this idea. Were we watching a documentary on Ted Bundy at the time?).

I'm glad I still have this paper and my other groundbreaking reports. They bring back good memories. But this minnow one might have to be destroyed. I still don't want any prosecutors having access to it.

A place to read about life in New York City, life in small Minnesota towns haunted by dolls, publishing, newspapers, writing, classic sports events and more.

Friday, July 30, 2010

Wednesday, July 28, 2010

Books from the basement, Volume I

Visiting the family in Minnesota. Have already hit the Dairy Queen. Whined about Dick Bremer. Complained about the humidity. And tonight I engaged in my twice-a-year trip to my parents' basement, where you can find birth certificates, obituaries, congratulations on graduations and sympathies for deaths. There are tax forms, toys, golf clubs and magazines. And books.

Boxes of my parents' books. And boxes of my own books. I still have about eight or nine boxes crammed with hardcovers and paperbacks taking up space in the back area known simply as the junk room. Junk is such a harsh word, though. And misleading, especially when it comes to the books. Someday we'll have to take these back and find space for them and Louise might curse that day, but for now they still sit where they've been for half a decade, safe and secure in their cardboard homes. On every trip back to the Midwest, I like to dig through them for lost treasures and old memories. Sometimes I'll take one home. Usually I read it and return it.

Tonight I pawed through some old sports ones. I found several copies of the old The Complete Handbook of Pro Basketball, which came out every year, profiled each team and player, provided predictions and presented feature stories from NBA writers around the country. I think I bought one every from 1985 through at least 1991. Before each NBA season, I'd scour the Mankato B. Dalton bookstore for the latest issue. As far as I know they're no longer published. Zander Hollander edited the books. The biographies of each player were always my favorite section. These bios praised the greats and buried the worthless. The tone was sarcastic and snarky, long before the latter word became the default setting for way too many writers.

The one I'm looking at now is the 1989 edition. Magic Johnson and Isiah Thomas grace the cover. They're kissing. It's a picture from the previous year's finals, when the two guards and then good friends shocked many with their Morganna-like greetings before each contest. The handbook features stories on Mark Jackson, who was an outstanding point guard long before he started rattling off increasingly annoying phrases involving words like "momma," "there," "goes," "that," and "man." There's a story on great love matches in athletic history, a tongue-in-cheek analysis of the Magic-Isiah coupling. There's a fun collection called the All-Flea Market team, Jan Hubbard's picks for various teams, such as the All-Big-Mac team, which was filled with large fellas like John Bagley, Pearl Washington and Antoine Carr.

The experts picked the Lakers to defeat the Celtics in the Finals, but the Pistons and Magic Johnson's balky hamstring dashed those predictions.

The biographies of each player were the highlight of every handbook. Behold:

Bill Wennington: A great cheerleader. Has excellent technique waving his towel from the bench. Now you know why we don't go to Canada to look for more basketball players.

Uwe Blab: They say he's a long-term project. At the rate he's progressing, he'll be ready to contribute in the league right about the time he qualifies for Social Security. A matching bookend of uselessness for the last two years with Bill Wennington on the bench.

Joe Barry Carroll: A prolific promulgator of polysyllabic palaver. In other words, he likes to use big words. Fancies himself as a real intellectual. It would be nicer if he just worked harder at playing basketball.

Allen Leavell: Like a bad cold, he keeps coming back. As long as he is a starter or a significant performer, then you know his club cannot contend for a championship.

But the profiles gave credit when required. For Michael Jordan, coming off a season where he averaged 35 a game but a few years before everyone started calling him the best ever, the editors wrote, "Words don't do him justice. No one on this team should ever grumble a syllable about him." (Yes, sometimes teammates grumbled about Saint Michael). In Magic's section, it reads, "There is Magic and there is Larry Bird and nobody else is in their class." (that nobody, at the time, included Jordan.)

Still, it's always more fun reading ridicule:

Benoit Benjamin: Sometimes you get the feeling that you'd be better off with the Statue of Liberty playing center.

Jon Sundvold: He looks so cute and lovable, you want to hang him from your rear-view mirror. He'd probably do about as much good there as he would making any NBA club a real contender.

Artis Gilmore: Should hang it up before someone gets killed.

The books really disliked bad centers - Artis, Benoit, Wennington, Blab, Joe Barry - and they had a lot to choose from. Like...

Granville Waiters: This guy never got off the bench in the playoffs. Bulls were eliminated. A connection? Be serious. He's slow, can't jump and is not aggressive. Was a free agent and the Bulls came to him last summer. "They said they needed me," he said. They never said for what.

Greg Dreiling: Stiffer than Julius Caesar. Should be a law passed prohibiting people from wasting seven feet of height.

Stuart Gray: See Greg Dreiling and wasted height. (Gray and Dreiling both played for Indiana at the time. Not that the Pacers had a thing for drafting tall, white guys, but their first-round draft pick that year? Rik Smits. At least Smits could play.)

Danny Vranes: Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus. Santa dresses as an NBA businessman and hands out $520,000 contracts to guys like this who average 2.1 points a game.

There was a player named Bob Thornton. He played for Philadelphia when this book came out. He wasn't good. The bio: "Now starting for your Minnesota Timberwolves..."

The Timberwolves were still a year away from joining the league. And, in 1991, Bob Thornton played 12 games for the Wolves. I think the book also predicted the career of Ndudi Ebi.

How can I ever throw a book like this away? I can pick up this 1989 version - or any of the basketball ones, or any of the baseball and football editions - and entertain myself for 90 minutes, reading about bad white centers and below-average middle infielders who should have stayed on a bus in Double-A ball.

No, I'll never toss them, though Louise might do just that some day. It'd be a crime to discard these books, as the world would lose the immortal entry:

Keith Lee: Mr. Disappointment. He didn't play a minute all year with leg injury that resulted in surgery. Probably his best season as a pro.

Monday, July 26, 2010

Lightning and other natural disasters in New York

Two really cool videos taken in New York City on Friday night. The first one shows the most famous skyline in the world being lit up with the type of storm you normally associate with the plains of Oklahoma or the prairies of Minnesota. The second video shows the lightning bolts emerging from the sky, followed by the torrential rains that blanketed the boroughs. It's the types of scenes that conjure up words like apocalyptic, at least when they happen in New York. The storms rolled through the city shortly before 9 p.m. I boarded a bus in New Jersey at 8:10 p.m. and was on the A train in Manhattan by 8:35. It was dry in Jersey. By the time I stepped out of the subway at 207th Street in upper Manhattan, the rain had started to fall.

Because I forgot an umbrella when I left the house nine hours earlier, I cursed the gods and my own incompetence. I stopped at McDonald's to pick up some dinner. By the time I stepped out of the restaurant five minutes later, the rain had turned into a downpour. Lightning decorated the sky in every direction. By the sound of the thunder, it seemed like the storm was centered directly over Inwood, maybe over the local 99-cent store, maybe over our apartment building. I'd never seen a storm like this during my time in New York. It reminded me of the storms that precede tornado warnings in Minnesota. The cities hit the sirens, meaning it's time to find a basement, though many people use them as a signal to step out on the porch or into the car to see what all the excitement's about.

"Wanna go find the storms?" is an actual question sober people ask their friends and family.

With my McNuggets and fries jammed into my black bag, I sprinted six blocks to our apartment, avoiding puddles while searching the sky for bolts. An ear-piercing thunder strike - which brought about cries of "Holy Shit! Let's get into the subway!" from a group of four cowering men - actually made me jump higher than I have since grabbing a rebound my senior year of basketball.

My run took me past a city park, which means my run took me under some trees, which means my run freaked me out for about 30 seconds. Good god, do not go under a tree during a storm. How many times have I heard that over the years? A hundred? Two hundred? I finally made it home, soaked but safe. Only later did I learn that a woman got struck by lightning around this same time in the Bronx. A man got drilled in Brooklyn. Both, fortunately, survived. Only later did I learn that there had actually been a tornado warning issued for New York City, an occurrence that is seemingly as rare as a hurricane warning for Minneapolis. But tornadoes have actually hit the city. A twister did severe damage to Brooklyn in 2007 - the first tornado to hit Brooklyn since 1889. There have been some brief touchdowns in Staten Island. Manhattan seems immune.

Except in the movies:

Are trailers about scary movies supposed to look and sound like an Onion News Video?

There were no tornado terrors in NYC on Friday night, but it was as close to the real thing as possible, minus the funnel clouds.

One thing I actually love about living in New York is that we are, for the most part, immune to natural disasters. We're in Manhattan, so we should be safe from tornadoes. Even Hollywood has only been able to come up with laughable scenarios like the one above to document the threat. If it did ever happen and you were going to describe it as being something out of a movie, you'd have to be much more specific: "It looked like something out of that hideous 2008 movie starring Nicole de Boer."

Experts always say a hurricane could one day strike New York. Call me complacent or naive, but hurricanes still aren't something I worry about. Blizzards hit the city, but during my six years in New York I've learned that if you don't have to drive in the treacherous weather - and driving through whiteout conditions in rural Minnesota is often a great time for internal conversations like, "God, if you do exist, and you get me out of this alive, I promise to live a better life" - blizzards really aren't too bad. We don't worry about earthquakes or tsunamis.

We're safe from natural disasters here. Man-made horrors delivered by terrorists are another story. But even with those I operate on the assumption that it's pointless to worry about something that's out of my control and I fear those as much as I fear a tornado strike. Being naive is occasionally a good way to go through life.

I've often thought about where the perfect city would be to avoid natural disasters. Minnesotans loathe blizzards. They fear being caught on the road during one and swear at meteorologists who deliver news about them, but they accept them as a part of life. You usually have two or three days warning. When they survive them, they talk about the storms with pride, or compare them to blizzards from two decades earlier so they can say, "You know, when I was younger, our blizzards were ten times worse than this. This was nothing." But tornadoes terrify. They can emerge from nowhere, and the damage can be totally random. Tornadoes have completely destroyed small towns, flattening every home and business. But they can also hit larger cities and crush an entire neighborhood, while leaving one house standing in pristine condition. For the first seven years of my life we didn't have a basement. When the Janesville sirens blared, we hustled into the car and drove to my dad's aunt's house. There we huddled under the pool table, riding the storm out. Basements feel safe. But while they can protect human life, they do nothing to prepare people for the heartbreaking damage they often encounter above when they emerge from below.

The entire Midwest faces these threats. So they're not ideal places to avoid natural disasters. Earthquakes, to me, are even more frightening. The randomness, the potential for collapses - from buildings and the ground. The stories we keep hearing about "The big one" that's bound to hit. Add it all up and the West Coast is no place to live, for those seeking to avoid Mother Nature's wrath. The south has its hurricanes. Idaho and Montana have...whatever Idaho and Montana have.

In the end, New York City is probably the best place for avoiding all of that, for avoiding earthquakes and hurricanes. It's the best place for dealing with snowstorms and it's the best place for avoiding tornadoes. At least, that's what I'll tell myself the next time I'm sprinting through lightning strikes and downpours.

Friday, July 23, 2010

Hunting for more treasures in the Sports Illustrated vault

Sports Illustrated's online vault remains one of my favorite spots on the Internet. The site remains free, though there are always rumors that someday Time-Warner may start charging for access to the incredible archives inside the vault. I'd pay. Then again, I still actually buy newspapers and I know that's a dwindling minority, so who knows if other people would fork over money for access to SI's treasured past.

Sports Illustrated's online vault remains one of my favorite spots on the Internet. The site remains free, though there are always rumors that someday Time-Warner may start charging for access to the incredible archives inside the vault. I'd pay. Then again, I still actually buy newspapers and I know that's a dwindling minority, so who knows if other people would fork over money for access to SI's treasured past.This cover above has John and Evelyn Olin, or, as they're called, "Mr. And Mrs. John Olin." It's from November 17, 1958. This issue came four years after Sports Illustrated premiered. It still focused on things like sailing, hunting and bridge. College football reigned, not the NFL. Baseball was certainly a popular subject, but no more so than the America's Cup.

Some of the stories in this issue:

Smile of Champions Recap of class-boat titles

Fair Game for Monsieur Louis "The chef at 21 can prepare anything from baby pheasants to black bear chops"

When Ely Deserted Culbertson Riveting story about contact bridge.

And it's fair to say Sports Illustrated originally targeted an elite readership. Today the Faces in the Crowd features high school phenoms, small-college standouts and the occasional middle-aged guy who won five straight league bowling titles in Alabama. In this issue?

"Pierre du Pont III, Wilmington, Del. corporation executive, sailed his schooner Barlovento over rainswept 100-mile Chesapeake Bay course, won Skipper Regatta in corrected 17:25:05.

Yes, he's one of the Du Ponts. A normal guy. Just your average face in the crowd.

There was another story in the issue, a completely non-sexist feature called "The Question: Should a husband try to teach his wife to ski?" There's an answer from Gary Cooper (who says yes), and from Mrs. Nelson A. Rockefeller, who wrote, "I think it's fine for a husband to teach his wife to ski, providing, of course, that he himself is a good skier and a good teacher." Rockefellers on skiing, Du Ponts on sailing. All that's missing is a blurb about a Mellon heir dominating croquet.

SI always loved dogs, as evidenced by this odd cover. Or this one. And then there's the February 8, 1960 cover: Are Dog Shows Ruining Dogs? I say yes.

In its early years, Sports Illustrated often relied on drawings for its covers, like this Masters one. The week after that issue, the "6th Annual Baseball" issue also featured a sketch, not a photo. In the May 16, 1960 issue, SI boldly labeled Australia the "leading sports nation," and as proof featured a cover of half-naked men and over-dressed girls playing tennis.

The old Sports Illustrated just loved bridge. Noted bridge expert Charles Goren appeared on the cover twice and had a cover byline a third time. Goren's byline appeared on the February 17, 1964 issue, the last time bridge graced the SI cover.

By the 1970s, SI had drifted toward the major sports, though the magazine still saved countless pages for national track and field events and regional swimming competitions, the type of stories that basically only appear every four years today.

By the 1970s, SI had drifted toward the major sports, though the magazine still saved countless pages for national track and field events and regional swimming competitions, the type of stories that basically only appear every four years today.

Fran Tarkenton was the first Viking to make it on the cover, in 1962. Sports Illustrated's famous NFL writer Tex Maule wrote the cover story on the young quarterback, who would be traded by the team five years later before returning to Minnesota in the 1970s for the team's glory years. Maule's story ran with the headline "His Sundays are Murder: Fran Tarkenton, quarterback of the Minnesota Vikings, has to scramble to save his young life." The second Viking player to make the cover? Ron Vander Kelen. A year after publishing the story on Tarkenton, SI wrote a lengthy feature on the rookie quarterback Vander Kelen, who came to the Vikings after playing college ball at Wisconsin and winning the Big Ten MVP in 1962. The story ran in August, as the rookie adjusted to the pros. Vander Kelen did not exactly match his college success; he threw six touchdown passes in his career. He's probably best known for being a trivia question answer: who started at quarterback in Bud Grant's first game as Vikings coach?

Incidentally, Bud Grant never made it on the cover of SI. In other words, Charles Goren made it two more times than one of the most successful coaches in NFL history. Then again, Charles Goren never lost four Super Bowls.

So many great strange covers from the magazine's early decades. Bud Ogden played two years in the NBA. He scored a total of 257 points. Yet in 1969, Ogden, then a star at Santa Clara, made the cover of the most famous sports magazine in the land, in this artsy, odd cover shot that was apparently conceived by a photographer who was enjoying some of that decade's finest pharmaceutical products:

In the current SI, there's a story on Atlanta manager Bobby Cox. But in 1957, a different Bobby Cox became the first Minnesota sports figure to make the Sports Illustrated cover. The magazine declared Gophers quarterback Bobby Cox the best quarterback in America. As far as I can tell, Cox is the only Gopher football player to ever make the cover. And, based on the last fifty years of Gophers football, it's more likely SI will put a bridge player on the cover before a Gopher.

But at least the program doesn't have to worry about being jinxed.

By the 1970s, SI had drifted toward the major sports, though the magazine still saved countless pages for national track and field events and regional swimming competitions, the type of stories that basically only appear every four years today.

By the 1970s, SI had drifted toward the major sports, though the magazine still saved countless pages for national track and field events and regional swimming competitions, the type of stories that basically only appear every four years today.Fran Tarkenton was the first Viking to make it on the cover, in 1962. Sports Illustrated's famous NFL writer Tex Maule wrote the cover story on the young quarterback, who would be traded by the team five years later before returning to Minnesota in the 1970s for the team's glory years. Maule's story ran with the headline "His Sundays are Murder: Fran Tarkenton, quarterback of the Minnesota Vikings, has to scramble to save his young life." The second Viking player to make the cover? Ron Vander Kelen. A year after publishing the story on Tarkenton, SI wrote a lengthy feature on the rookie quarterback Vander Kelen, who came to the Vikings after playing college ball at Wisconsin and winning the Big Ten MVP in 1962. The story ran in August, as the rookie adjusted to the pros. Vander Kelen did not exactly match his college success; he threw six touchdown passes in his career. He's probably best known for being a trivia question answer: who started at quarterback in Bud Grant's first game as Vikings coach?

Incidentally, Bud Grant never made it on the cover of SI. In other words, Charles Goren made it two more times than one of the most successful coaches in NFL history. Then again, Charles Goren never lost four Super Bowls.

So many great strange covers from the magazine's early decades. Bud Ogden played two years in the NBA. He scored a total of 257 points. Yet in 1969, Ogden, then a star at Santa Clara, made the cover of the most famous sports magazine in the land, in this artsy, odd cover shot that was apparently conceived by a photographer who was enjoying some of that decade's finest pharmaceutical products:

In the current SI, there's a story on Atlanta manager Bobby Cox. But in 1957, a different Bobby Cox became the first Minnesota sports figure to make the Sports Illustrated cover. The magazine declared Gophers quarterback Bobby Cox the best quarterback in America. As far as I can tell, Cox is the only Gopher football player to ever make the cover. And, based on the last fifty years of Gophers football, it's more likely SI will put a bridge player on the cover before a Gopher.

But at least the program doesn't have to worry about being jinxed.

Wednesday, July 21, 2010

Joe Mauer is no Jake Taylor

A six degrees of separation type thing happening tonight. Or something.

Four days ago, character actor James Gammon died at the age of 70. Gammon might have been best known as playing the grouchy Lou Brown, the hard-scrabbled manager who improbably leads the Cleveland Indians to a division title in the classic movie Major League.

Tonight I saw Inception. Tom Berenger has a role in it. Berenger, of course, played grouchy catcher Jake Taylor, the veteran, over-the-hill tough guy whose guts and grittiness help the Indians to the title in Major League.

Tonight the Twins played the hapless Indians.

In the movie, Jake Taylor wins the one-game playoff against the hated Yankees with a surprise bunt down the third-base line. The winning run comes around from second to score.

Tonight, Joe Mauer stepped up to the plate with the score tied and runners on first and second. To the surprise of, well, everyone but the Major League screenwriter, Mauer bunted. He failed. The Indians got out of the inning a batter later. The Indians won the game. The Twins mourned. Their fans cursed. Writers wailed.

If Mauer was indeed inspired by a movie, couldn't it have been The Natural instead?

Now, if the Twins follow the plot to Major League II, next season Mauer will take over as interim manager for an ill Ron Gardenhire and lead the team to the AL pennant. And that really doesn't sound any more improbable than Mauer's bunt.

Four days ago, character actor James Gammon died at the age of 70. Gammon might have been best known as playing the grouchy Lou Brown, the hard-scrabbled manager who improbably leads the Cleveland Indians to a division title in the classic movie Major League.

Tonight I saw Inception. Tom Berenger has a role in it. Berenger, of course, played grouchy catcher Jake Taylor, the veteran, over-the-hill tough guy whose guts and grittiness help the Indians to the title in Major League.

Tonight the Twins played the hapless Indians.

In the movie, Jake Taylor wins the one-game playoff against the hated Yankees with a surprise bunt down the third-base line. The winning run comes around from second to score.

Tonight, Joe Mauer stepped up to the plate with the score tied and runners on first and second. To the surprise of, well, everyone but the Major League screenwriter, Mauer bunted. He failed. The Indians got out of the inning a batter later. The Indians won the game. The Twins mourned. Their fans cursed. Writers wailed.

If Mauer was indeed inspired by a movie, couldn't it have been The Natural instead?

Now, if the Twins follow the plot to Major League II, next season Mauer will take over as interim manager for an ill Ron Gardenhire and lead the team to the AL pennant. And that really doesn't sound any more improbable than Mauer's bunt.

Tuesday, July 20, 2010

The one game Michael Jordan didn't get any calls

People regularly call Michael Jordan the best basketball player to ever live, and if they don't say that they at least call him one of the two or three best. But those adjectives weren't always used with his name.

In 1985, Jordan won the Rookie of the Year award. He had a fabulous season, averaging 28 points per game on a bad Bulls team that won 38 games. He electrified the league with his tongue and his dunks. He became the best-selling shoe salesman in the greater Chicago area.

In February of that year, the Bulls hosted the Lakers, the defending Western Conference champions who were seeking redemption from the previous season's Finals humiliation, which ended with thousands of Boston hooligans - many of them shirtless - storming the court at the Game 7 buzzer. But the playoffs were still three months away. This was just another winter game in a cold city against a below-average team. But any game involving Magic, Kareem, and Michael will never be just another game.

Jordan guards Magic from the outset. The Lakers enjoyed some mismatches - like, say, Kareem against Dave Corzine. Jordan's actually sporting fairly short shorts in this one, he hadn't yet started wearing the baggy pants he'd help make famous and standard. Jordan starts off hot, but Magic and the Lakers slowly take over - Magic, not Michael, actually dunks first. Jordan then picks up a pair of fouls. There are a couple of Magic no-look passes, plays he made look routine but the types of passes you almost never saw from anyone else then and rarely see today. One goes to Kareem, then a superb fastbreak at the 3:20 mark.

Then, history at the 3:55 mark. Jordan gets called for a reach-in touch foul on a 20-foot jumper by Michael Cooper. It's his third foul of the half and he sits after scoring 14. Jordan played 14 more seasons. I'd almost guarantee that after this season he never again got called for this type of foul. He barks at the ref, which he'd expertly do the rest of his career. And he probably even said, "You can't make that call against me." This might have been the last time a ref disagreed with that assertion.

The Lakers lead by an absurd 73-63 score at the half. Jordan struggles throughout the second half, missing layups when not being denied the ball by Byron Scott. Bob McAdoo rejects him at one point. Jordan's teammates - immortals like Corzine, Wes Matthews and Rod Higgins - fail to pick up the slack. At the 6:45 mark, Jordan gets called for another ridiculous foul, his fifth, the type of call refs might make on Jeffrey Jordan, but never Michael. It's bizarre watching a game where Michael Jordan does not get the calls. Not even that. He's actually being screwed by the refs, as if he was Rasheed Wallace with better hair. It's jolting, but enjoyable. The Lakers pick apart the Bulls, with Kareem's hooks, Magic's drives and passes and a goggles-less James Worthy's swooping layups.

How bad was Jordan? After scoring 14 points in the first half, he scores his first point - on a free throw - with 42 seconds remaining in the game. The announcers talk about the youngster trying to maintain his poise. They talk about how he's a great player but he just didn't have it tonight. Michael Jordan. World's greatest, but just another frustrated, lost rookie on this night. He might have been the best ever, but that wasn't always so.

The game was also a tribute to the Lakers defense. They were one of the best offensive teams in basketball history, but they could also play some defense when it mattered. Jordan didn't have any help in this game, but he didn't have any help all season and he still averaged 28 a game. The Lakers didn't just take his teammates out of the game, they took him out of it.

And that's the way this 1985 regular season game ended. The Lakers cruising to a 127-117 victory. Magic starred, Jordan suffered. Byron Scott played outstanding defense. God, I wish I could write those words about the 1991 Finals instead.

Sunday, July 18, 2010

Professors: Ease up on chemistry and math students

Did you know that English majors are smarter than chemistry majors? And education majors are brighter than math majors? It's true, at least according to GPAs.

A recent study by Wake Forest University analyzed grade point averages at an unnamed liberal arts school. The five majors that had the lowest GPAs were chemistry (2.78), math (2.90), economics (2.95), psychology (2.98) and biology (3.02). The five highest GPAs came from education majors (3.36), language (3.34), English (3.33), music (3.30) and religion (3.22).

The study reports that students get discouraged early by the tough grades in those majors and drop out for ones that offer the chance for higher GPAs. So people are debating whether professors should perhaps ease up on the grading in those disciplines, since the world needs more scientists, engineers and mathematicians. If the students can get through the early courses, maybe they'll stick with it for four years.

Thankfully I never had to take a chemistry class in college. A roommate took organic chemistry, which was regarded as perhaps the toughest course at St. John's. The roomie and his somewhat odd chemistry buddies - who appeared to have sniffed too much butane - gathered each week for marathon study sessions while I spent time playing Tecmo and writing my 10-page papers a day before the due date. I felt bad for them, even if a few of the guys gave off an uncomfortable vibe. They seemed like the type of people who might one day have the New York Times publish their poorly punctuated manifesto.

Another roomie took high-level math classes. He spent eight hours working on a single proof, absurd problems that left him drained but ultimately proud when he solved them. I'd go play basketball with the other roommate and we'd leave Mike at his desk, his head buried in his hands. When we'd return two hours later, he'd be in the same position. We'd leave for dinner and come back an hour later, only to find him still seated, still holding his head in his hands. It was no way to live. Still, the guy owns his own company today, so the hard work paid off, even though I don't think he makes much use now of his ability to solve 10-hour math problems.

I thrived in math through elementary school. I dominated in the flash-card multiplication game. Things started going bad in about eighth grade, which was about the time I decided to be a reporter when I grew up. State regulations were the only reason I took any more math classes.

At Worthington, I took calculus and trigonometry, the victim of a transfer coordinator at St. John's who insisted I had to take those classes before leaving community college. Each day I went into the classroom thinking, "This is the day I'm going to really listen. This is the day I will figure out what trigonometry is all about." And each day I stared at the board in disbelief, struggling to understand a professor whose fourth language was English. The night before my trig final, I spent all night studying, trying to cram in 10 weeks of information. The plan failed.

Once I finally arrived at St. John's, I learned I could take a math theory class and I spent a semester breezing through it, writing papers about famous mathematicians. That still didn't make up for the suffering I endured taking calculus and trigonometry, nor did it provide relief for the professors who graded my exams in those two classes. I didn't test well in those courses - in the finals or during the semester. Professors probably carried my exams over to their colleague's office so they could mock my answers while mourning for the future of the country.

"Can you believe this kid didn't know how to obtain a positive coterminal angle? God. And just look at how he tried to prove the law of sines. Look at it."

I majored in communications at St. John's, which included the journalism courses. It's not listed as being among the easiest majors for GPAs, which I find a bit surprising. I took several challenging classes at St. John's and had a couple of brilliant professors who were also hard-asses when it came to grading papers and tests. But overall it wasn't the most difficult of majors.

St. John's requires students to take a couple of religion classes. I breezed through one of mine, bored the entire semester. But the other one challenged me every day and actually made me interested in the Old Testament. The professor graduated from the Harvard Divinity School and was probably the second most-brilliant person I ever encountered in school. His passion inspired all the students, even atheists and agnostics. I say second most-brilliant because the smartest person I saw in school was one of the students in that theology class, a guy named Phil. Each day Phil sat in his chair, long legs stretched out in front of him, goofy hat on his head. He majored in theology. He battled the professor, debating theories and facts. The arguments usually sailed over the heads of everyone else in the class, but they still fascinated us. If Jesus had walked into class one day and heard Phil talk, he would have pulled up a seat and thought, "Now that's something I never thought about." Phil was probably a genius, even if, like other religion majors, he likely benefited from grade inflation.

By the time I turned 14, I knew I didn't have a future as a scientist, a chemist or an engineer. My college grades only reaffirmed that belief. But for those wide-eyed nerdy students who enter those disciplines only to find themselves crushed by impossible tests and low grades, I express my sympathy. I urge them to stick with it. Grades aren't everything. Besides, if the really smart people invade English, education, journalism, and language classes, all they're going to do is ruin the curve for the rest of us.

Friday, July 16, 2010

Witty headline goes here

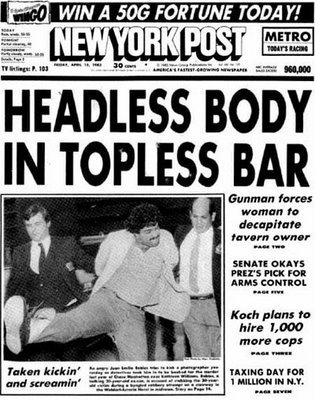

Pulitzer Prize winner Gene Weingarten wrote a column for the Washington Post about the lost art of writing headlines. Like circulation and ad dollars, headlines - good ones - are becoming a victim of online media. As papers transition to the web (don't people use the word transition as a euphemism when people die? Anyway.), witty, clever, amusing and outrageous headlines are no longer needed, or even desired. Instead, as Weingarten wrote, headlines are now "designed for search engine optimization." Great. Paper versions can still deliver the goods, but fewer people see the hard copy version so fewer readers get to appreciate the creativity of copy editors, who are usually seen as a dour group of people only obsessed with proper use of commas.

When I worked as a newspaper copy editor, we wrote the headlines and I liked that part of the job more than anything. We also designed the pages, and some people enjoy that aspect more. But give me the headline writing.

It's not as fun if you're on a news desk. Earthquakes, budget deals and city council meetings rarely lend themselves to creative headlines. Also, copy editors on the news desk often write headlines for stories about investigations. Investigations into politicians and corrupt cops. Investigations into bankers who embezzle and dads who write bad checks. Investigations into college basketball players who cheat on tests and coaches who cheat on their wives. Unfortunately, there are very few synonyms for "investigation." And, for the most part, there's only one similar word that fits into a small one-column space: Probe. And copy editors hate using the word probe. It conjures up images of alien abductions and doctor visits that end with a punchline and humiliation. But no matter how much they dislike the word, a news copy editor will inevitably use the word probe in a one-column headline and probably once a month.

Senate

launches

Goldman

probe

Police

probe

burglaries

Yuck. Back to fun headlines. In sports you get away with more, within reason. A colleague of mine once wrote the headline: FLIP'S FLIP FLIPS FLIP'S WOLVES

Personally, I thought it was genius. Flip Murray tossed in a lucky shot at the buzzer to defeat the Timberwolves, coached by Flip Saunders. Another editor thought it was a bit too much.

The highlight of my time on the sports desk at The Forum in Fargo was when one of our headlines made The Tonight Show, years before everyone hated Jay Leno and stopped watching his show. Most of the headlines Leno displays are mistakes or a typo or an unfortunate picture choice. We knew ours had a chance to get on the air. A few weeks after publication, Leno showed it on his show. This was more thrilling to a copy editor than catching an award-winning reporter misusing there and their.

A writer at the paper, Terry Vandrovec, came up with the headline. All I did was type it onto the page:

FRIKKEN LAYUP DOOMS BISON

The story was about a basketball player named Frikken, who hit a game-winning shot to defeat the North Dakota State men's basketball team. We exchanged high-fives in the newsroom that night.

An old editor of mine, Bob Van Enkenvoort, won an Associated Press award when he penned the perfect headline "Mmm, mmm, goodbye" when the Campbell's Soup factory closed in Worthington.

I still have a dusty file that contains some of my clippings, including old headlines. I have a printout from 2003, when our sports editor sent around a list of some of the department's best headlines of the year, as we debated which ones to enter for competitions.

If I may, some of mine that were up for consideration:

UDDERLY AMAZING (about a kid who owned a dairy herd, had a 4.0 GPA and was a great basketball player. Come on).

BACK ON THE HORSE (gymnastics coach returns to powerhouse he built years earlier)

DEAR JOHN (Feature about a beloved wrestling coach named John who retired)

TWINS PLAY CREDIT CARD (Twins were whining about lack of respect while facing Yankees, who then dispatched Minnesota in the playoffs, proving everyone right, unfortunately)

ANOTHER YANKEE DANDY (Clemens dominates Twins)

HOT COCO BURNS COYOTOES (Player named Coco has big basketball game)

SPANDEX SWAPPER SPARKS SPUDS (Former swimmer became a top-notch wrestler)

And on and on. Some of them are certainly a bit cheesy. But that's part of the fun. Copy editors rely too much on movie and book titles. They rely too much on possibly cliched sayings, but they use them in a way that's usually ironic and puts a new spin on an old line.

You bring readers in with the headline, then tell the real story in the dek right below, then follow with the reporter's story. An older reader used to call periodically and a few times he wanted to know who wrote a particular headline, because he enjoyed it so much. Most of the times readers call to demand why the newspaper hates high school swimming. Or they asks us if we know we possess below-average intelligence. So calls like the headline lover's boost the self-esteem of copy jockeys.

Living in New York, of course, affords me the opportunity to see true headline-writing geniuses at work. I read the Daily News and New York Post every day. Without fail, each paper delivers superb headlines in every edition. I savor papers like The New York Times because of the in-depth reporting and I subscribe to magazines like Esquire and The New Yorker because of the 10,000-word feature stories. But when it comes to summing up a story, a scandal, an arrest, a death or a victory in a short headline, no one competes with the tabloids. Several years ago I had a tryout at the New York Post. It didn't result in a job offer, but during my tryout, I did get to pen a headline that ran with one of the sports section's main stories. It was a simple Mets game story, but it involved Pedro Martinez pitching against the Nationals and Jose Guillen. A game earlier, Pedro had plunked several Nationals hitters, including Guillen. But on that night he shut Guillen down, and the Nationals. The headline: NO WAY, JOSE. Nothing spectacular. An old saying. But seeing it in the next day's newspaper in a giant font gave me a thrill.

Copy editors don't get any credit and if there's a mistake they get all the blame. Many readers think reporters write their own headlines, which proves convenient when an irate subscriber calls in to complain about a headline that "your reporter" wrote. But it also means they don't get the kudos for a superbly crafted headline. And in today's media world, those opportunities are dwindling.

In the big picture, the loss of great headlines obviously isn't the same as the loss of jobs and even entire newspapers. But if newspapers ever do go completely online and great headlines disappear, it means papers would be a little less fun to read. And they'd be a hell of a lot less fun to work at.

UPDATE: Added a link in the post to the Leno clip of The Forum headline. And it's here.

Wednesday, July 14, 2010

Whatever happened to Mildred, Ernest and Cyril?

Stumbled across this classic George Carlin bit, where the late genius comic ridicules names like Todd, Cody, Kyle and Tucker, while lamenting a world with fewer guys named Eddie, Vinnie and Tony.

Every year the Social Security Administration releases the list of the most popular baby names. On their website, you can analyze name data going back to 1880, a time when Harry, Walter and Minnie ruled. Spending time on there is like wandering around the Baseball or Basketball Reference sites. A quick 10-minute trip can turn into an hour-long journey.

Selfishly, I first wanted to know where Shawn ranked. I didn't want it to be too popular; I didn't want to be a commoner. In 2009, it was the 210th most popular name for boys, down from 195 in 2008. Shawn didn't appear in the Top 1,000 rankings until 1947, when it appeared at 922. In 1964, it finally broke into the Top 100, coming in at No. 88 (the audio version of this blog post will be read by Casey Kasem or, failing that, Rick Dees). Its best ranking ever came in 1973, when it was 27th. In 1975, the year I was born, it was 31st. The name has been dropping in popularity ever since. In 1975, Shawn was also the 254th most-popular name for a girl. In college a friend tried setting me up with a girl named Shawn. I begged off, fearing that an eventual marriage - if, you know, it reached that point after a few dates - would lead to a household with two people named Shawn Fury. This leads to ridicule, which I know because our school's old band instructor was named Kim Lau, as was his wife. Kids mocked this, though the reasons why this was so funny remain a bit unclear.

Sean is a more popular spelling than Shawn, as it was ranked 97 in 2009. I remain forever grateful that my parents chose the correct way to spell my name.

The first data comes from 1880, when John and Mary topped the charts. Today they are ranked 26 and 102, respectively. John held the top spot from 1880 through 1923, a dynastic run that dwarfs anything accomplished by Russell's Celtics or Wooden's Bruins. It didn't fall out of the Top 5 until 1973, a remarkable streak. It's never returned. Obviously, Baby Boomers fell slightly out of love with the name and it's never recovered.

My grandpa's name was Cyril, one of those old-sounding names that seems unimaginable for a kid today. Picture some 8-year-old named Cyril running around a youth soccer field today. Imagine his mom yelling, "Cyril, you're going home with the Johnsons, we'll pick you up later." Hard to do. If you know a Cyril today, chances are he was alive during the first World War.

Grandpa was born in 1913, when Cyril was ranked 302. Cyril never broke the Top 200 and since 1966 it's never even been in the Top 1,000. My mom's name is Cecelia, and she does spell it with the middle e (like her grandma did, whom she was named after), though everyone calls her Cees. Cecelia - with an e - is a pretty rare name, coming in at 738 in 2009. Cecilia - with an i - was at 265. I might be biased but I like it with an e, even though three generations of Simon and Garfunkel fans - and Saint Cecilia - are convinced it should be with an i. Great song, wrong spelling. And Cees - which, as I wrote, is what everyone calls my mom; most people probably don't even know it's short for Cecelia - has, according to the SSA website, not been "in the top 1000 names for any year of birth in the last 130 years." Now that's a name with a sense of uniqueness.

Know many Mildreds? Probably not. And if you do, it's likely because of visits to a nursing home or touching newspaper stories about a couple's 75th wedding anniversary. As recently as 1945, it was in the Top 100. She's been out of the Top 1,000 since 1984. Unless a retro-name craze hits the country, she will surely never return.

The months are interesting. Between 1976 and 1979, January cracked the Top 1,000 each year. But it never did before '76 and never since '79. This makes no sense to me. What occurred in 1976 that made people want to name their daughter January, and what happened to make that desire disappear after a four-year stretch? April's been around since 1939, peaking at 23 in 1979 (a big year for the months). But now it's down to 353. May, there's another old name, one you'll probably only see in Remember When columns that date back to the 19th century. May was the 95th most popular name in 1901 but hasn't been in the Top 1,000 since 1982.

A name to keep any eye on: June. As recently as 1941, June ranked 90th. Then it plummeted out of the Top 1,000 from 1987 through 2007. But June came back in 2008, placing 867. And in 2009, it was 662. So in two years, it inexplicably jumped at least 338 spots. It seems like it's a name that would appeal to people. Simple, conjures up images of warmth and sunshine. Could June break the Top 500 in 2010? The Romans were apparently more popular in the 19th century, as August was in the Top 100 for 12 years. It fell into the 900s in the 1980s, but has bumped up to 433.

Jayden ranked No. 8 in 2009, which can perhaps partially be blamed on Britney Spears giving her second child that name, inspiring others with her wise life choices. It didn't make the Top 1,000 until 1994 and even then it was 851. It took off in popularity at the same time as the Internet. Was there some type of online campaign to name children Jayden? Every year since it improved position. It seems inevitable that it will someday hold the top spot, a remarkable ascension for a somewhat ludicrous name.

The No. 2 name for boys - Ethan - has also had a startling rise. It was no higher than 263 until 1989. But it's now been in the Top 5 since 2004. That at least makes sense, I know an Ethan. I do not know any Jayden's or August's. Isabella reigns for the girls. In 1989, Isabella wasn't in the Top 1,000. Twenty years later, No. 1. I need a sociologist to comment on what all this means.

My wife likes to say she's a unique person and when it comes to her name, she's definitely correct. Louise hasn't been in the Top 1,000 since 1991. Like many names that are no longer as popular, Louise started falling in the 1940s - it ranked 99th in 1948. Even the Greatest Generation apparently thought their names sounded old - when they started naming their children, Cyril, Millie and Ernest began disappearing from birth certificates.

In the battle of seasons, Autumn rules, coming in at 81, well ahead of Summer at 175. As for Spring and Winter, they only made appearances in the 1970s. Spring cracked the Top 1,000 between 1975 and 1979, while Winter made it in 1978 and '79. Odd. Why those two years? Were fears about a nuclear winter so prevalent during the Cold War then that the word stuck in people's heads when naming their daughters?

And as for George Carlin and his dislike of Todds around th,e world, the late comic might have had an impact on some people. Todd was the 454th most popular boys name in 2001, when Carlin ranted about the name in his Complaints and Grievances concert. Today, just a decade later, it's at 892 and seems on its way out of the Top 1000. Maybe it's just a coincidence, but maybe not. Maybe Carlin bullied some people into forgoing Todd.

Carlin died in 2008. Too bad he's no longer around, because we need someone to take on Jayden.

Carlin died in 2008. Too bad he's no longer around, because we need someone to take on Jayden.

Sunday, July 11, 2010

Use your writing skills to make a buck an hour

When I first started working at newspapers, I always grumbled about writing certain stories. Bowling results, for example. Love participating in the sport, despite the germ-infested shoes and even though I'm so inferior at it I've literally been defeated by a 5-year-old girl (it was bumper bowling, which somehow makes it worse, since I lost despite not having any gutter balls). But writing up weekly reports about the happenings at the local alley always seemed tedious and somewhat pointless.

But eventually you learn that at a newspaper - especially a small daily and especially when you're just starting and don't know anything even though you think you know everything - it's a skill to be able to write about anything, and a necessity. Whether it's track and field agate or dance team, everything you write matters to someone, even if you think it shouldn't matter to anyone. You learn how to write about a wide variety of subjects and take pride in it. You work for a valuable organization and that helps you keep your self-respect, through the horrible hours and worse pay.

Freelancers have a tougher life. Pride is not always a luxury they can afford. They have to endlessly search for jobs, especially freelancers who aren't writing feature pieces for magazines or respectable websites. There are thousands of people who make a living doing low-paid work that is surely beneath their skill set. Maybe they write about napkins. Or write college essays about William Randolph Hearst for frat boys who are too drunk to turn on their computer the night before a 10-page paper is due. Freelance writing: a glamorous life.

Here are some of the latest job atrocities available to eager freelancers.

Writer for title and job description. A job title and description that doesn't read like a title and doesn't have a description. Very 1984, Newspeakish. I spent 20 minutes trying to figure out what the job entailed. I still don't know. Which means I lack the technical ability that will be so critical for all writers in the next decade and beyond. Damn it.

"Basically, you will be writing the main Title and Description for my niche websites. These should not take more than 10 minutes to do, I am looking to pay someone $1 for writing 2 titles and descriptions for the topic I give you."

Here's an eight-minute youtube video about the job that has replaced Ambien and Jay Leno's monologue as America's leading sleep-aid. The person posting this ad notes that he set his budget at $5. Say one lucky freelancer lands that whole budget. Those five bucks would perhaps - but not likely - be enough to buy a single Prozac tablet the freelancer would need to work through the depression that sets in once the paycheck from the job appears in his bank account.

The same person has posted other jobs, ones that he filled. Like this one to be a "blog commenter." Description:

"I need you to comment on blogs. I will give you the blog post to comment on, but you will have to double check and see if the comment backlinks are 'dofollow.' Only apply if you have experience in commenting."

It's one dollar for every 10 posts and a candidate should expect to comment on 100 posts in a week. So, you're looking at 10 bucks a week. Hey, it could be beer money, at least. And by beer money I mean - if you live in Manhattan - you can buy a single beer and have two bucks left for a tip.

Here's a mysterious job: When applying, all applicants "must start their replies with 'Halloween Project' or they will not be considered." Halloween Project? It sounds like a CIA codename for an attempted coup in a South American country that will go into motion on October 31. The job actually entails writing about costumes for various websites. It's estimated to be a 30-hour-a-week gig, with the budget set at a precise $65. So two bucks an hour, or, twice as much as you'd make writing comments on 10 blogs focused on the majesty and mystery of Halloween costumes. See, freelancers do have options. The poster is a stickler for manners, as every reply must end with Thank You. If you end it with Thank You Very Much, you might be eligible to make $67 for the project.

For you business writers...Five-year strategic plan writer.

"I am looking for someone to write a five-year strategic plan for a fictional company. I have 17 pages of data and information on this fictional company, which you will have access to. The strategic plan should include background, major issues and specific recommendations in detail."

Okay. When reading that, this scene came to mind.

Here's a job that at least sounds like it could be entertaining, even if the wages are the type normally associated with overseas shoe factories. Writer for movie rumors and news.

"I need 5 articles on movie rumors and news per week for the next 8 weeks."

So basically you'll be writing movie news. And rumors. Nothing in there says the rumors have to be accurate. So...

1. Leonardo DiCaprio has reportedly pulled out of talks for the Titanic sequel.

2. A 35-year-old man in New York City stood in something sticky during a viewing of the delightful Knight & Day. Who was he, and what was the substance?

3. When Arnold Schwarzenegger leaves office, don't be surprised if The Governator reprises his role as John Matrix in a remake of Commando. Steven Spielberg is tentatively scheduled to direct.

4. No one in Hollywood wants to go on the record, but it's looking more and more like Godfather IV will be a reality. Marlon Brando will star, thanks to CGI technology.

5. As part of his contract, Wilford Brimley insists on performing all his own stunts.

Five rumors, that's 50 cents right there.

In a few years maybe there won't even be a job called freelance writer. Instead, everyone will be freelance tweeters, which sounds less like a job and more like a part-time recreational drug user. Yes, you're a great writer. You wowed your mom with that essay about ponies in the third grade and you have a 900-page novel set during the fall of the Berlin Wall that you're certain will make you a literary superstar. But in the meantime, to pay the therapy bills, there's this job, where you'll "write simple tweets, will provide urls where you can get the information for the product, from there you will write the tweets. Must be a good writer and know how to sell. ...Our budget for 500 tweets is $12."

In today's world, where teachers and professionals regularly bemoan the writing abilities of students and employees - which is what happens in a land of lol, omg, wut, :), and roflmao - you'd think people who can string sentences (and sometimes even paragraphs) together would be valuable workers. Apparently not.

There are obviously worse jobs out there and being a writer is still a pretty good way to make a living. Yes, there are worse jobs. But there might not be any worse-paying professions.

But eventually you learn that at a newspaper - especially a small daily and especially when you're just starting and don't know anything even though you think you know everything - it's a skill to be able to write about anything, and a necessity. Whether it's track and field agate or dance team, everything you write matters to someone, even if you think it shouldn't matter to anyone. You learn how to write about a wide variety of subjects and take pride in it. You work for a valuable organization and that helps you keep your self-respect, through the horrible hours and worse pay.

Freelancers have a tougher life. Pride is not always a luxury they can afford. They have to endlessly search for jobs, especially freelancers who aren't writing feature pieces for magazines or respectable websites. There are thousands of people who make a living doing low-paid work that is surely beneath their skill set. Maybe they write about napkins. Or write college essays about William Randolph Hearst for frat boys who are too drunk to turn on their computer the night before a 10-page paper is due. Freelance writing: a glamorous life.

Here are some of the latest job atrocities available to eager freelancers.

Writer for title and job description. A job title and description that doesn't read like a title and doesn't have a description. Very 1984, Newspeakish. I spent 20 minutes trying to figure out what the job entailed. I still don't know. Which means I lack the technical ability that will be so critical for all writers in the next decade and beyond. Damn it.

"Basically, you will be writing the main Title and Description for my niche websites. These should not take more than 10 minutes to do, I am looking to pay someone $1 for writing 2 titles and descriptions for the topic I give you."

Here's an eight-minute youtube video about the job that has replaced Ambien and Jay Leno's monologue as America's leading sleep-aid. The person posting this ad notes that he set his budget at $5. Say one lucky freelancer lands that whole budget. Those five bucks would perhaps - but not likely - be enough to buy a single Prozac tablet the freelancer would need to work through the depression that sets in once the paycheck from the job appears in his bank account.

The same person has posted other jobs, ones that he filled. Like this one to be a "blog commenter." Description:

"I need you to comment on blogs. I will give you the blog post to comment on, but you will have to double check and see if the comment backlinks are 'dofollow.' Only apply if you have experience in commenting."

It's one dollar for every 10 posts and a candidate should expect to comment on 100 posts in a week. So, you're looking at 10 bucks a week. Hey, it could be beer money, at least. And by beer money I mean - if you live in Manhattan - you can buy a single beer and have two bucks left for a tip.

Here's a mysterious job: When applying, all applicants "must start their replies with 'Halloween Project' or they will not be considered." Halloween Project? It sounds like a CIA codename for an attempted coup in a South American country that will go into motion on October 31. The job actually entails writing about costumes for various websites. It's estimated to be a 30-hour-a-week gig, with the budget set at a precise $65. So two bucks an hour, or, twice as much as you'd make writing comments on 10 blogs focused on the majesty and mystery of Halloween costumes. See, freelancers do have options. The poster is a stickler for manners, as every reply must end with Thank You. If you end it with Thank You Very Much, you might be eligible to make $67 for the project.

For you business writers...Five-year strategic plan writer.

"I am looking for someone to write a five-year strategic plan for a fictional company. I have 17 pages of data and information on this fictional company, which you will have access to. The strategic plan should include background, major issues and specific recommendations in detail."

Okay. When reading that, this scene came to mind.

Here's a job that at least sounds like it could be entertaining, even if the wages are the type normally associated with overseas shoe factories. Writer for movie rumors and news.

"I need 5 articles on movie rumors and news per week for the next 8 weeks."

So basically you'll be writing movie news. And rumors. Nothing in there says the rumors have to be accurate. So...

1. Leonardo DiCaprio has reportedly pulled out of talks for the Titanic sequel.

2. A 35-year-old man in New York City stood in something sticky during a viewing of the delightful Knight & Day. Who was he, and what was the substance?

3. When Arnold Schwarzenegger leaves office, don't be surprised if The Governator reprises his role as John Matrix in a remake of Commando. Steven Spielberg is tentatively scheduled to direct.

4. No one in Hollywood wants to go on the record, but it's looking more and more like Godfather IV will be a reality. Marlon Brando will star, thanks to CGI technology.

5. As part of his contract, Wilford Brimley insists on performing all his own stunts.

Five rumors, that's 50 cents right there.

In a few years maybe there won't even be a job called freelance writer. Instead, everyone will be freelance tweeters, which sounds less like a job and more like a part-time recreational drug user. Yes, you're a great writer. You wowed your mom with that essay about ponies in the third grade and you have a 900-page novel set during the fall of the Berlin Wall that you're certain will make you a literary superstar. But in the meantime, to pay the therapy bills, there's this job, where you'll "write simple tweets, will provide urls where you can get the information for the product, from there you will write the tweets. Must be a good writer and know how to sell. ...Our budget for 500 tweets is $12."

In today's world, where teachers and professionals regularly bemoan the writing abilities of students and employees - which is what happens in a land of lol, omg, wut, :), and roflmao - you'd think people who can string sentences (and sometimes even paragraphs) together would be valuable workers. Apparently not.

There are obviously worse jobs out there and being a writer is still a pretty good way to make a living. Yes, there are worse jobs. But there might not be any worse-paying professions.

Thursday, July 8, 2010

The writing life

An old refrain among newspaper reporters is that everyone has a story. It means a gas station attendant could have a tale in his life that's every bit as fascinating as the life of a U.S. senator. It's just a matter of reporting and finding the details - both big and small - that make a great story. This isn't always necessarily true. Giggling 13-year-old gymnasts who serve as ventriloquist dummies for hyperactive stage moms do not always have a good story. But most people do.

In the past few months, I've also learned that everyone has a novel. And there's a decent chance it's a novel about a vampire or a werewolf or life in Regency England or a demon that emerged from the sun's rays. It very well might be about a cop - probably divorced, likely an alcoholic, certainly grizzled. It could be about a cop who's a vampire. Or a cop who's a vampire in Regency England.

Everyone has a novel, and I've learned this because Louise is a literary agent. She focuses on romance, young adult, middle grade, pop culture, and steampunk. But she's always on the lookout for anything good, regardless of genre.

The agency she works at - like all agencies - receives a constant barrage of submissions, from published authors to those who only have a dream and a keyboard. The agents wade through the unsolicited emails, which usually include the synopsis and a few chapters. Manuscripts come from all over, from all walks of life. They arrive from penthouses and prisons. They arrive from 20-year-old boys and 70-year-old women, all of them just hoping for that one break that leads to a contract and a cover. Agents spend a lot of time fulfilling dreams, but they spend just as much time breaking hearts.

If the agents like something, they ask for the full manuscript. That's with fiction. Nonfiction, I think, is a little easier, at least from the writer's perspective. There, like I did with my book, you need the idea and perhaps a few sample chapters, not the whole book. On the other hand, it could be tougher for an agent to sell just an idea to a big publishing house. How do they know a writer can pull off what they propose? With fiction, an agent can send an editor a knockout book - about a vampire, or a menacing cop, or a grizzled werewolf - and the publisher knows what they're getting, they know right away if it's something they want, if the author can deliver.

Two things strike me when reading some of the submissions: the sheer number of them, and the incredibly diverse backgrounds of the writers. Retired doctors ask if they can send in a 99,000-word pirate adventure story they've been working on for years. Yeah, yeah, they've saved lives, but what they've wanted to do for 30 years is write.

Housewives send in their 110,000-word science fiction epic, a novel they wrote while raising five kids and one husband. They have ambition, certainly - the dream of being published is a powerful one and partly explains why I wanted to be a newspaper writer from about the time I was 11 years old. But most of the people have to understand the odds are against them ever seeing their work in the local bookstore, no matter how many times you read something and think, I could do that.

Housewives send in their 110,000-word science fiction epic, a novel they wrote while raising five kids and one husband. They have ambition, certainly - the dream of being published is a powerful one and partly explains why I wanted to be a newspaper writer from about the time I was 11 years old. But most of the people have to understand the odds are against them ever seeing their work in the local bookstore, no matter how many times you read something and think, I could do that.

So the avalanche of submissions isn't simply about the dream of being published. They write their romance novels or middle grade fiction because they have a story to tell and they want to write it. They want to create new worlds and characters, they want to dive deep into their own imagination and discover what emerges. Everyone has a story. And everyone seemingly has a story to tell.

Is telling stories a human instinct? Long before there were books, people told stories out loud, passing them down from generation to generation, tales that imparted life lessons but also ones that entertained. I don't know how many of the people find time in their incredibly busy lives to carve out these stories, many of which are outstanding and simply need someone in the business to push it to a publisher. In their pitches, you can sense how much they care about the work, how they've slaved over creating fictional they sent on amazing adventures. When reading an especially good line or paragraph, you can envision them at their kitchen table, late at night, after a long day of work at the office, long after the kids have been put to the bed, writing the sentence and thinking to themselves: That's a good line. And you see them hoping that someone else will read it and think the same thing.

Not that all the pitches or manuscripts are good. Many are bad. Some are inexplicable - I have nothing against midgets, sex, angels or midgets who died while having sex and became angels, but I don't know if I, or anyone else, would want to read an entire book focused on that storyline. Sometimes it seems the people with the worst chance of being published have the most confidence, bordering on arrogance. I'm envious of that self-belief. The self-confidence of the delusional is often a powerful thing.

But even with the people whose pitches to an agency or publisher probably never have a chance, I still admire the courage it takes to send your work out to strangers, to professionals who will judge it. I know the nerves that can hit with every query and every published article. I know what it's like to wait for reviews. But I don't know the satisfaction that comes from working on novel for five years and hearing, "We want it." And I don't know the crushing disappointment that comes from working on a novel for five years and hearing, "Thanks, but no thanks."

The people who pitch agents believe in their heroines and their villains. They believe in their complicated plots and simple sentences. And I do admire all of them.

People say the book industry is in trouble. Many believe books are doomed for extinction, perhaps around the same time the last newspaper rolls off the printing press, only to be discarded by a bored 22-year-old. Yet nearly every time I'm in a bookstore, it's crowded. I'm now convinced that all of those people crowding the aisles have a file on their computers back home, an unfinished romance or the first of a proposed eight-part science fiction series. They love writing, and love reading. Maybe the statements in that sentence will be enough to save the industry.

No matter what the future holds, people will still want to tell their stories, whatever the format. Writers of all ages and abilities work hard and they dream big. They think their books are outstanding, and some of them are even right.

They all have a story, all right. And it's 90,000 words long.

Not that all the pitches or manuscripts are good. Many are bad. Some are inexplicable - I have nothing against midgets, sex, angels or midgets who died while having sex and became angels, but I don't know if I, or anyone else, would want to read an entire book focused on that storyline. Sometimes it seems the people with the worst chance of being published have the most confidence, bordering on arrogance. I'm envious of that self-belief. The self-confidence of the delusional is often a powerful thing.

But even with the people whose pitches to an agency or publisher probably never have a chance, I still admire the courage it takes to send your work out to strangers, to professionals who will judge it. I know the nerves that can hit with every query and every published article. I know what it's like to wait for reviews. But I don't know the satisfaction that comes from working on novel for five years and hearing, "We want it." And I don't know the crushing disappointment that comes from working on a novel for five years and hearing, "Thanks, but no thanks."

The people who pitch agents believe in their heroines and their villains. They believe in their complicated plots and simple sentences. And I do admire all of them.

People say the book industry is in trouble. Many believe books are doomed for extinction, perhaps around the same time the last newspaper rolls off the printing press, only to be discarded by a bored 22-year-old. Yet nearly every time I'm in a bookstore, it's crowded. I'm now convinced that all of those people crowding the aisles have a file on their computers back home, an unfinished romance or the first of a proposed eight-part science fiction series. They love writing, and love reading. Maybe the statements in that sentence will be enough to save the industry.

No matter what the future holds, people will still want to tell their stories, whatever the format. Writers of all ages and abilities work hard and they dream big. They think their books are outstanding, and some of them are even right.

They all have a story, all right. And it's 90,000 words long.

Wednesday, July 7, 2010

If LeBron acts like Dennis Green the whole absurd event will be worthwhile

A short post, in honor of LeBron's press conference, the most highly anticipated sports moment of the year and the most highly anticipated moment in pop culture since 12 people decided OJ's fate 15 years ago. Great moments from press conferences past. Because sports is no longer about what happens on the court, it's about who gets courted off of it. Exciting times for sports fans.

And with Jim Gray being charged with the heroic task of interviewing LeBron after the decision - sorry, The Decision - here's a look back at everyone's favorite sideline reporter.

We can only hope that Gray also asks LeBron to apologize for putting everyone through these past few traumatic weeks.